Enenuru explores Adab

In beginning our overview of scholarship on the Sumerian city of Adab

(the modern site of Bismaya), we first quote from a scholar particularly

important to the study of this site - Karen Wilson served as curator

and then director of the Oriental Institute Museum in Chicago, her service

there lasted 15 years. She has undertaken a project to assemble all

the remaining unpublished material that remains from the site, much

of it stored in Chicago, and we hope to see this book published in the

near future; in the mean time we have presented below Wilson's brief

synapsis which contains an excellent discussion and also conveys briefly

some important understandings regarding the limits of what can be said

about Adab's history (especially given the uncomplete state of scholarship

on Adab materials):

(

From the 2004 Bismaya overview, Karen Wilson )

The purpose of this project is to analyze, interpret, and publish the important discoveries made by a University of Chicago expedition in 1903-1905 at the site of Bismaya (ancient Adab) in what is now south-central Iraq (31°54' N, 45°36' E; see attached map). The excavations were first directed by Edgar J. Banks and then, briefly, by Victor S. Persons. Over 1000 artifacts, many of them early cuneiform documents, were sent to Chicago, where they are now housed in the Oriental Institute Museum.

The results of the Bismaya excavations were never properly published, and most of the material was never published at all. Banks' relationship with the University of Chicago soured after cessation of the work, and neither he nor Persons ever prepared a scientific presentation of their results. Banks wrote a lively and highly readable popular account, Bismya [sic.], or the Lost City of Adab-a mix of travelogue and archaeological narrative-that appeared in 1912 and included only a small fraction of his finds, with almost no analysis of their original contexts. Most of the material from Bismaya remains unknown, despite the fact that Adab was a major city at the dawn of Mesopotamian history. Banks excavated one of the earliest known Mesopotamian temples and discovered some of the world's first historical royal inscriptions, incised on stone vessels dedicated in that temple beginning as early as 2550 B.C. He also excavated an administrative center, a residential quarter, and what he described as a palace with a library, all of the Akkadian period (ca. 2335-2155 B.C.), a slightly later cemetery and residential area, and portions of the city wall.

Since 1912, little attention has been paid to this material, and Bismaya has been largely forgotten. This project will rectify this situation and will result in the complete presentation of this large and significant corpus of unpublished material. The proposed monograph will include analyses of stratigraphy, architecture, sculpture, cylinder seals, metalwork, and pottery, and discussions of chronology, the succession of the first kings of Adab, administrative practices during the third millennium B.C., and methods of artistic and symbolic representation. This "reexcavation" of Bismaya using the weekly reports that both archaeologists sent back to Chicago, Banks' daily field diaries (which are surprisingly detailed given that they date to the infancy of Near Eastern archaeology), and the artifacts housed at the Oriental Institute Museum is of immense value not solely because of the importance of Adab and its early date. In recent years, looters digging in search of antiquities have all-but-destroyed the site. Thus, whatever can be learned about the history of the city and those who lived and ruled there resides in the records and objects now in Chicago.

Adab in Seals and Signs

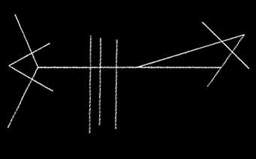

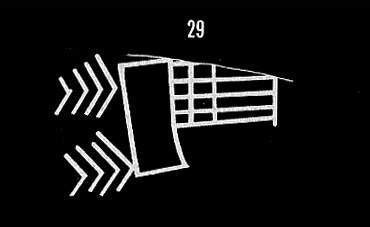

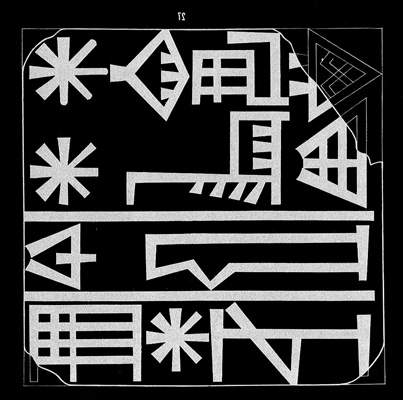

Archaic city seal of Adab

Above we have displayed the City Seal Adab, which likly served to distinguish

products from that city within early Sumerian intra-city trade networks.

The example above was found at Ur and appears in Leon Legrain´s

"Ur Excavations III , Archaic Seal Impressions,

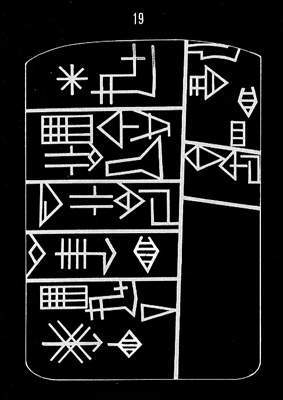

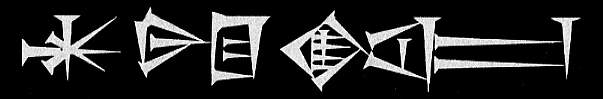

1936". Directly below, we have included examples of

the City name as it appears in Archaic Cuneiform script (note the resemblence

to early city seal design - for more on city seals and their relation

to geographic name in cuneiform script, please see Link).

Adab ud-nun-ki

History of Adab

mu adab ki hul-a / "The year Adab is destroyed" (a year name of Rimush)

In considering the History of Adab, we have been extremely grateful to Yang Zhi who has taken a rare interest in the topic and presented an excellent volume entitled "Sargonic Inscriptions from Adab" (1989). To begin the examination of what is sometimes termed the "lost city" of Adab here at enenuru, we first refer heavily Zhi's commentary in order to present a sketch of the cities history from the Early Dynastic to the Ur III periods. Additional considersations to follow below.

"Sargonic Inscriptions from Adab" (1989) , Yang Zhi

Yang Zhi on Adab in the Early Dynastic period

Unlike later periods or the Early Dynastic period in Lagash, from which

genuine historical inscriptions have survived, the Early Dynastic sources

from Adab give only isolated names of rulers. Because of this, the study

of the history of Adab in this period is still in the primnitve stage

of trying to determine the sequence of the local rulers, of whom we

know next to nothing. The only king of Adab mentioned in the Sumerian

King List is Lugal-ane-mundu. According to the King List, his reign

should belong to the Early Dynastic period.

[according to votive inscriptions found on site] the rulers of Adab

were the following:

Nin-kisal-si GAR.énsi

Me-ba-dur Lugal

Lugal-da-lu Lugal

Bará-hé-i-dùg GAR.énsi

Muk-si GAR.énsi

É-igi-nim-pa-è GAR.énsi

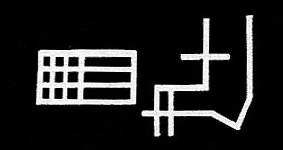

Inscription of É-igi-nim-pa-è

A note on Ruler titles

It is tempting to use the titles of rulers as a criterion for dating

the Adab rulers, since the writing GAR.énsi looks like an archaism.

But the GAR.énsi title in Adab was used consistently from the

time of Nin-kisal-si down to that of E-igi-nim-pa-è, who would

be closest to the Akkadian era.

Elsewhere, the same title was used by Sá-tam, Ruler of Uruk,

during early Sargonic times. It therefore seems clear that the GAR.énsi

title is not an archaism, but simply a (regional?) pecularity.Concerning

the list i have drawn together above, i have not included in it the

ruler named Lum-ma, despite the fact that his name is found on two votive

inscriptions from Adab (A208 and A 217),one of which describes him as

PA.SI.GAR. Lum-ma´s title was written PA.SI.GAR and PA.GAR.TE.SI,

instead of the standart GAR.PA.TE.SI of the other Adab rulers; his title

was never followed by the qualification "of Adab". These data

would seem to indicate that Lum-ma was not a local ruler of Adab, but

a ruler from another city who placed votive vessels in the E-sar temple.

Reconstructing Early Kingship in Adab

1. There were two temples in the early history of Adab: É-sar and É-mah. The archeological evidence from Bysmaya makes it sufficiently clear that É-sar was an earlier temple with a limestone foundation and that É-mah was a later temple with a foundation of planoconvex bricks, built on top of the ruins of É-sar. Textual evidence supports this sequence, since, of the two, É-mah was the temple mentioned in the Old Akkadian period. The rulers and their votive inscriptions associated with the temple É-sar should be earlyer than ruler(s) associated with the temple É-mah. The former group includes Nin-kisal-si, Me-ba-dur, and Lugal-da-lu, while É-mah was built by É-igi-nim-pa-è and appears in the inscription of no other ruler. This puts É-igi-nim-pa-è toward the end of our list of rulers and the end of the Early Dynastic period. This point is supported by the shape of É-igi-nim-pa-e´s bronze tablets (OIP 14 19-22), which is very close to that of the Old Akkadian tablets, i.e., rectangular with one side flat and other convex, quite different from the Early Dynastic tablets from Adab.

É-sar

É-mah

2.In earlier period, the signs on a tablet were not necessarily written in the same sequence in which they were read. This can be seen in the temple name É-sar, which was written as SAR.É in the inscriptions bearing the names of Nin-kisal-si, and Me-ba-dur. The name was written É-sar in the inscriptions of Lugal-da-lu and Bará-hé-i-dùg. While not definitiv proof, this circumstance suggests that Lugal-da-lu and Bará-hé-i-dùg probably date after Nin-kisal-si, Me-ba-dur.

SAR.É

3. According to OIP 14 5, Nin-kisal-si was contemporary with Mesilim, the king of Kish. Mesilim was contemporary with Lugal-shà-engur, the second earliest ruler known from Lagash, who can be dated to ca. 2550 B.C. This would put Nin-kisal-si about the same date. So he may be the earliest attested ruler of Adab.

4. The recently published text UCLM9-1798 proves that the ruler Muk-si probably preceded É-igi-nim-pa-è.

Kesh and cult in early Adab

The newly published text UCLM9-1798 provides an important piece of new

information on the history of Adab at the end of the Early Dynastic

period. This text records the sale of land of the heirs of the priest

of Kesh to the GAR.énsi of Adab, É-igi-nim-pa-è.(

as Foxvog points out at "Funerary Furnishings" in "Death

in Mesopotamia" several serious problems of interpretations still

remain. My understanding of the text is that Bíl-làl-la,

the priest of Kesh, died, and his heirs, who did not bear any priestly

title, sold the land to the GAR.énsi of Adab. The GAR.énsi

of Adab, É-igi-nim-pa-è, paid for the land with barley

that came form the house of Muk-si, his predecessor, and the temple

of Nin-muk.He also paid five mina of silver to the brothers of Làl-la,

the wife of Bíl-làl-la, who was already dead at the time

of the transaction and was buried in URUxA, probably her home town.

This was so that Làl-la could be released from URUxA and reburied

with her husband. The transaction was not a private one on the part

of É-igi-nim-pa-è, since he made the payment with property

from a temple and its precedessor´s house. On the part of the

seller, however, there is a lack of cultic personnel witnesses except

for one a-tu, a priest of the Ninhursag cult. It is probable that this

was not because the sale was a purely personal matter of Bíl-làl-la´s

heirs, but because Bíl-làl-la was the last priest of Kesh.)

This evidence ties together several data concerning the history

of the cities of Adab and Kesh. First, according to earlier literary

tradition, we know that Kesh was the cultic center for the mothergoddess

Ninhursag, but that later Adab displaced Kesh.[editors

note: here we note a line from "The Lament for Nibru" which

reads: The Anuna, the lords who decree fates, order that Adab should

be rebuilt, the city whose lady fashions living things, who promotes

birthing!] Secondly, we know the place name Kesh had practically

disappeared by the Old Akkadian period. Thirdly we know that É-igi-nim-pa-è,

the buyer of the land in this text, was the builder of É-mah,

the larger temple which replaced the older É-sar in Adab. Putting

all of this together, i would propose that the center for the cult of

Ninhursag was formally transferred from Kesh to Adab at this point in

history, marking the end of Kesh as a cultic center.

Ninhursag

The rise of Adab as an important cult center also coincided with the rise in the number of Akkadian personal names. This ocurred especially during the time of the last two énsis of the Early Dynastic period. The exchange of gifts with Lagash under one of the last two rulers, the building of the new temple É-mah, and the purchase of land from the priest of Kesh by É-igi-nim-pa-è all indicate that Adab was prospering prior to the Akkadian conquest.

Yang Zhi on the Old Akkadian period in Adab

Adab during the reign of Sargon

Sargon, who called himself king of Akkad and king of Kish, was probably partly contemporary with En-sha-kush-anna, a ruler originally from Ur who was recognized in Nippur as "King of the land." In addition, we know that Sargon was contemporary with Lugalzagesi, the ruler of Umma who called himself "King of Uruk" and "King of Sumer." Sargon conquered Lugalzagesi and then left him to rule as énsi, a post Lugalzagesi continued to hold into the reign of Rimush.

The ruler of Adab at the time of Sargon and Lugalzagesi was Meskigal. Meskigal called himself énsi and Lugalzagesi lugal. This shows that before Sargon conquered Lugalzagesi, Adab was under Umma´s influence. Just how much authority the "King of Sumer" had over other citystates, however, is not clear.

According to Sargon´s inscription b 1, he first conquered Uruk

and captured Lugalzagesi; then he fought against Ur, É-nin-MAR

ki, Lagash, and Umma. There is no information on Adab during the reign

of Sargon, after he conquered Lugalzagesi.

Though Sargon states that he conquered Ur, Umma, and Lagash, and his

year names tell us that he also conquered Elam, Urua, and Mari, his

control over these cities did not last. His successor, Rimush, in turn,

had to reconquer Ur, Umma, and Lagash, and also battle against Kazallu,

Adab, Zabalam, and a region in Elam called Barahsi. The chronological

order of these conquests is not clear from his various inscriptions.

Adab during the reign of Rimush

During the reign of Rimush, while this Akkadian king still calls himself "King of Kish", Ka-Ku of Ur was called "King of Ur" and was the only ruler in Sumer using the title lugal. The rulers of the other sumerian cities which Rimush fought were énsis and were presumably under the leadership of another center, probably Ur. For Adab, this would have meant that, after the previous overlord Lugalzagesi of Umma had been subjugated by Akkad, Meskigal had not automatically fallen under the authority of Akkad, but had either formed a small league with neighbouring Zabalam and recognized no overlord (i.e. called nobody "King") or had become part of the newly formed Ur-league.

According to Rimush inscription b 4, in the battle with Adab and Zabalam, the Akkadian soliders struck down 15,718 men, captured 14,576 men, captured Meskigal, the énsi of Adab, and Lugal-Ushumgal, the énsi of Zabalam, and sent an unknown number of men to labor camps. If Rimush´s numbers are not merely fanciful, Adab and Zabalam would have been radically drained of manpower. It is not known what happend to Meskigal after his capture.

From the reign of Manishtusu, we have no records mentioning Adab.

Adab during the reign of Naram-Sin

Naram-Sin´s gold leaves and brick stamps found in Adab are the earliest attestation of the Akkadian kings in Adab. Despite his unsubstantiadet claim to "nine battles in one year," Naram-sin´s reign was probably a turning point and time of recovery in sumer, following the upheavals which occured during the reign of his father and grandfather. Most cities within Sumer and Akkad had been conquered. According to his inscriptions and year names, Naram-Sin´s major campaigns were directed eastward towards Elam and Simurrum. Apart from this, he led an expedition westward to Ebla; dug numerous canals; established the foundations for the Enlil temple in Nippur and the Inanna temple in Zabalam; and built the Sin temple in Lagash. Naram-Sin broke also with tradition and was deified while he was still alive. This last act and the building of temples were probably political manoeuvres designed to win support of the old Sumerian city-states.

Naram-Sin

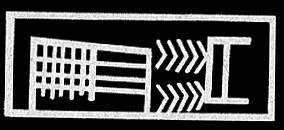

The brick stamp of Naram-Sin found in Adab states that Naram-Sin was the builder of the Inanna temple. The text does not state that the temple was in Adab. Since Adab and Zabalam were so close together, this may have referred to the Inanna temple in Zabalam and not a different Inanna temple in Adab.

Naram-Sin´s Brickstamp

The gold leaf (A1217) of Naram-Sin was found on mound V, the temple mound, where the temple É-mah stood in the Old Akkadian period. According to the excavation records, the É-mah which the Early Dynastic ruler É-igi-nim-pa-è built was of plano-convex bricks, while Naram-Sin´s gold leaf was found in a chamber of the temple built of long-grooved bricks, one level above the plano-convex structure. This would mean that sometime during the Old Akkadian period, most likely in Naram-Sins reign, É-mah was rebuilt. Adab was the center of whorship for one of the eight "great gods" Naram-Sin invoked in his deification inscription, namely Ninhursag. The gold leaf may have been part of an offering of Naram-Sin to Ninhursag.

We do not know the name of the énsi who ruled in Adab at this time. likely candidates are Ur-{d}dumu and the ésni whose name ends with the sign -AB. but the seal of Ur-{d}dumu does not state any allegiance to either Naram-Sin or his successor Sharkalisharri.

Adab during the reign of Sharkalisharri

Sharkalisharri´s era was generally a peaceful time, although

some unrest is indicated by his year names that mention battles with

Elam abd the Gutians, and the appearance of Amorites. Elamites had been

a consistent enemy of the Sargonic dynasty; the gutians were a new threat.

Though the foundation of Enlil´s temple in Nippur was said to

be laid by Naram-Sin, Sharkalisharri again claims to have laid the foundation

for the same temple. He left fewer royal inscriptions than Naram-Sin,

but many of his governors and subordinates left inscriptions and seals

stating their allegiance to him. Doubtless this was because the lower

levels of the "empire" were beginning to form a relativly

stable society, the result of the efforst of three generations of continuous

rule.

The local ruler of Adab during Sharkalisharri´s reign was the

énsi Lugal-gish. we do not know the name of his father, how he

came to office, or who succeeded him. His name does not appear in texts

outside of Adab. The archive from Adab in general does not contain much

information on political history. The most informative group of texts

we have consists of letters written by Lugal-gish, together with a memorandum

that a gutian general was passing through Adab on his way to Uruk.

(According to one of Shar-kali-sharri´s year names, the city of

Uruk (and Naksu) was the site of a battle. (RLA 2 133 f: MU REC169 unug

ki-a nak-su ki-a [] "Year in which the battle of Uruk and Naksu

[].) It is tempting to see a connection between the Gutian general going

from Adab to Uruk and this campaign by Shar-kali-sharri. Note that,

after the downfall of the dynasty of Agade, Utu-hegal, the restorer

of Sumer, mentions in his inscription both, Uruk and Nak-su ki. What

might inferred from these hints is that the city of Uruk seems to have

played a special role in the time of Gutian hegemony, perhaps having

been (peacfully?) infiltrated by Gutians during the Sargonic period

and dominated by them following the time of Shar-kali-sharri.)

Yang Zhi on the UR III period

Adab during the reign of Ur-Nammu and Shulgi

It is not clear whether Adab was under the rule of Ur as early as the

reign or Ur-Nammu. In his excavation records, Banks does not mention

Ur-Nammu, but in bismaya, he claims that one of the wells at mound IV

was built with stamped bricks of Ur-engur (Ur-Nammu). This information

without the bricks themselves to examine, or at least copies of one

of the brick inscriptions, is unreliable, and Ur-Nammu´s control

over Adab is still in question.

The ruler to follow Ur-Nammu, Shulgi,, built a dam in Adab for the goddesss

Ninhursag. Ur-Ashgi, an énsi of Adab, must have governed during

parts of Shulgi´s long reign. There is one fragmentary votive

inscription of this ruler probably dedicated to Shulgi (A 202=OIP 14

36); but we have no tablets bearing Ur-Ashgi´s own seal or name,

only the seal and name of his scribe Ur-pap-mu-ra. Ur-pap-mu-ra stayed

in office longer then his master. In Shulgi year 45, when Ur-Ashgi was

no longer énsi, Ur-pap-mu-ra stopped using the seal with the

énsi´s name on it and started using a seal which contained

only his own name and his father´s name.

According to two sealings (BR 3/1 13 and A 903), a person named Ur-Ashgi, the énsi of Adab had at least two sons: Lú-Utu and É-sa6-ga. The former´s seal was used in the year Ibbi-Sin 2 (A903). It is not clear whether Ur-Ashgi, the Adab énsi during Shulgis reign, was the father of these two, or was there an Ur-Ashgi II, who ruled during the later years of Shu-Sin and the beginning years of Ibbi-Sin. The first hypothesis would imply that Ur-Ashgi´s sons were still using their old seals with their father´s title on it, long after Ur-Ashgi´s removal from office. Apart from these two sealings, Ur-Ashgi´s name is also on a tablet and its sealing (UET 3 19). Unfortunately the year name of this tablet is only partially preserved: it can be Amar-Sin 5, 6 or 9, or less likely, Shulgi 29.

during the later kings of Ur

After Ur-Ashgi, the énsi at Adab was Ha-ba-lu5-ke4, whose name is not only attested on tablets frpm Adab, but also on tablets from Drehem and Ur.Amar-Shuba, the scribe of énsi Ha-ba-lu5-ke4, is well attested in the tablets in MVN 3. During Shulgi´s reign, Ha-ba-lu5-ke4 dedicated a stone bowl for the life of Shulgi (VA 3324). During Su-Sin´s reign, Ha-ba-lu5-ke4 built a palace for Shu-Sin, preumably in Adab. To judge from tablets from Adab itself and tablets from elsewhere mentioning Adab, Ha-ba-lu5-ke4 served as governor at least from the year Shulgi 39 (MVN 3 169) to Shu-Sin 3 (AOS 32 W 78). The best documented activities of Ha-ba-lu5-ke4 as city governor are his judging of legal cases involving citizens of Adab and his transactions with Drehem, the ancient Puzrish-Dagan, concerning animals.

The mechanism governing the receiving and dispatching of animals at Drehem still needs to be studdies in the context of the whole corpus of Drehem texts. The forty or so animal texts in this archive mentioning Adab may be divided into two types:

1. Records of animals going from Adab to Puzrish-Dagan. Most of texts belong to this type. They usually employ the terms mu-túm, ""brought in" and i-dab5, "took charge of." The number of animals involved is very small-- often only one, and in the largest case no more then thirty.

2. Records of animals going to Adab. These are, for the most part, characterized by the use of the verb ba-zi "extended." The quantity of animals going to Adab is much larger than from Adab (several tablets record more then 300 animals transferred). There are about half the number of tablets of this type as compared to the number of tablets of type "I".

We do not know who was énsi of Adab after year Shu-Sin 3, when records of Ha-ba-lu5-ke4 stopped. From Shu-Sin 8 and Ibbi-Sin 2, we have the sealings of the two sons of a Ur-Ashgi.

After Ibbi-Sin 2, Adab is not mentioned until the Isin-Larsa period. Banks´records indicate that more remains from the UrIII period may still be buried in Mounds IVa and VI of Adab.

HEAD OF A RULER

Gypsum, bitumen, blue paste (modern) H. 4 in. (10.16 cm.); W. 2 1/2 in. (6.35 cm.), D. 3 in. (7.62 cm.) Third Dynasty of Ur, ca. 2000-2050 B.C. Iraq, Bismaya Temple; OIM A173 Excavated by the Oriental Institute, 1904.

Male bust, perhaps Lugal-kisal-si, king of Uruk. Limestone, Early Dynastic III. From Adab (Bismaya). Louvre AO10921

Additional Resources

Notes on Administrative Texts from Adab

The three ox-drivers from Adab

Online Resources

Adab related online resources

Cuneiform Series, Vol. II: Inscriptions from Adab

Daniel David Luckenbill

-Bismya or The Lost City of Adab

-The three ox-drivers from Adab, ETCSL

-Digital images and Transliterations of 280 Adab tablets at University of Chicago

-A Previously Unpublished Lawsuit from Ur III Adab