The Shadow Side and

Prospects for Return

In the below reading, we continue notes on the Sumerian world

view - our intent is to consider the scholarship which has been

most effective in delimiting Sumerian notions of their world,

with the hope that this will help demystify aspects of the incantation

texts that are relient on native world view. Anyone just arriving

should first review the enenuru.net notes on the four winds, here

, paying particular attention to the easly dysnastic world maps

from Fara.

This time, we are focusing on the Netherworld concepts, and more

specifically, on the peripheral of the Sumerian world - that is

all that lies outside the Mesopotamian plateau, outside Sumerian

society itself and therefore outside the rule of the gods (as

it was the order and divine protection of the gods themselves

that contributed to the unique state of Sumerian cilivization,

according to the native view). All else was peripheral, disordered

and dangerous - the mountain gods, foriegn lands and wild animals.

These concepts of Sumerian worldview were best handled by Frans

Wiggermann in his article "Scenes from the Shadow Side"

(Mesopotamian poetic language: Sumerian and Akkadian, 2006). While

we will take notes on this article shortly, first from consideration

is given to D. Katz definition of the Sumerian netherworld, often

called by the name kur - and how kur (netherworld) and kalam (Sumerian

home country) contrast in native Sumerian thought. This understanding

will help as we come to Wiggermann's view.

The Kur-Kalam

contrast in Sumerian thought

KUR

KALAM

Wiggermann will state that "the most common term for the

Other World is kur, "mountain land", which is in opposition

to kalam, "our country". Referring to D. Katzm 2003

(The Image of the Netherworld in Sumerian Sources), she makes

some fine points which should embellish our concepts of Sumerian

Heartland and what can be termed broadly the "Other World".

She states that the term Kur became the most used word in denoting

the Netherworld in Sumerian literature - and yet, the word has

multiple meanings, it can mean as well "mountain" or

"foreign country". As Katz states, the contrast between

kalam and kur is both geo-physical and geo-political:

"The pair kur-kalam represent diametrically opposed concepts:

in relation to kalam, the heartland of Sumer in the alluvial plain

between the rivers, kur is the land that rises beyond its north

and northeastern boundaries. Both kur and kalam have two meanings

that are antithetically parallel to each other: from a geo-political

viewpoint kalam is "the land" (our homeland Sumer) as

opposed to kur "foreign land," and from a geo-physical

viewpoint kalam is the level land (of Sumer) as opposed to kur

the mountain area...In addition, the texts have positive connotations

contrary to the inimical attitude toward kur."

Kur as in Netherworld

The author speculates that it may have been this negative disposition

toward the kur land that lead the word to take on the second connotation

"hostile foreign land" or perhaps some combinations

of factors (certainly hostile foreigners such as the Gutians invaded

from this direction). How then did the word Kur come to have the

connotation Netherworld in the early Sumerian literature? - Katz

phrases this question more precisely as "how does the meaning

"Netherworld" emerge from the Bipolar Concept of Kur-Kalam?".

Her answer is that it is likely the original polarity between

kur-kalam extended, in early Sumerian mythological reasoning,

to a contrast between kalam as land of the living, and kur, as

the land of the dead.

If we don't know precisely why this was reasoned, we know that

it in any case was, due to the survival of early literature which

portrays characters traveling across land to the mountainous Netherworld.

Katz notes that this notion likely died out as early as the mid-third

millennium when exploration and territorial expansion would have

made a belief in kur as the netherworld unsustainable - although

some vestages of this notion continued in the literature (always

slow to change) new ideas of the netherworld as existing on a

vertical axis (i.e. underground) emerged with the Semitic inhabitants

of Mesopotamia. In any case, what is important here is to understand

kur (with it's different connotations) had an opposite polarity

as kalem in early Mesopotamian thought.

The Shadow Side

In Wiggermann's article "Scenes from the Shadow Side"

the author begins with a broad discussion on the subject of Mesopotamian

Cosmic Geography and the creatures thought to inhabit the fringes

of the known world. Attempts to understand the edges of the world

in a time before science and before reliable geographical information

frequently resulted in notions of the world which were, in part,

mythological. The Greek notion of cosmos is an example, on it's

fringes were thought to be imprisoned Giants and Titans, among

other things. Wiggermann will assert that this tension between

empirical geography and mythology is well attested in ancient

Mesopotamia as well.

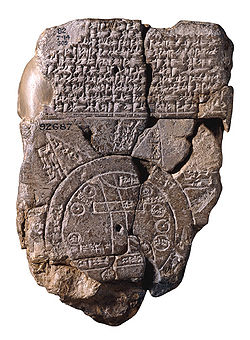

As mentioned, this review in part overlaps with material on the

enenuru four winds thread where we takes notes on cosmic geography

for that purpose as well - Wiggermann discusses maps from the

early dynastic period which notion of the earth as four sided

and surrounded by four rivers, the center of which is marked by

the great mountain of the god Enlil. This goes some of the way

in establishing that the Sumerians, like the Greeks and other

ancient peoples, entertained ideas of the world which were a mixture

of geographical observation and mythological deduction. For these

early dynastic maps, please refer to our four winds section. An

additional map that the author discusses, which is preserved on

a well known late Babylonian tablet called the Mappis Mundi (map

of the world):

In this map, Wiggermann says, "the cosmic river surrounding

the earth is called marratu, "ocean", and in the descriptive

part of the obverse it is explained as Tâmtu, "Sea',

the name of Marduk's arch-enemy in the Enuma Elish." In fact,

the map more or less represents the way in which Marduk settled

the bodies of his vanquished opponents here and there on the sea

around the world - and so, as the author implied early on, the

map thus demonstrates perfectly the tendency of ancient cosmology

to resort to myth in dealing with the fringes of the world. There

was effectively no barrior between empirical fact and mythological

fancy in the Mesopotamian world.

The Outer Regions and their

Inhabitants

From the 4th Millennium onward the Mesopotamians steadily (if

slowly) gained knowledge about the world around them - this included

both geographical insight, but also ethnological information (the

knowledge of close and distant peoples necessarily for extensive

trade). Wiggermann writes that the acquisition of this sort of

information is observable in a wide variety of Mesopotamian literature,

and as the Mappa Mundi indicates, results in a world view

which blends with mythology, theology, and impacts certainly on

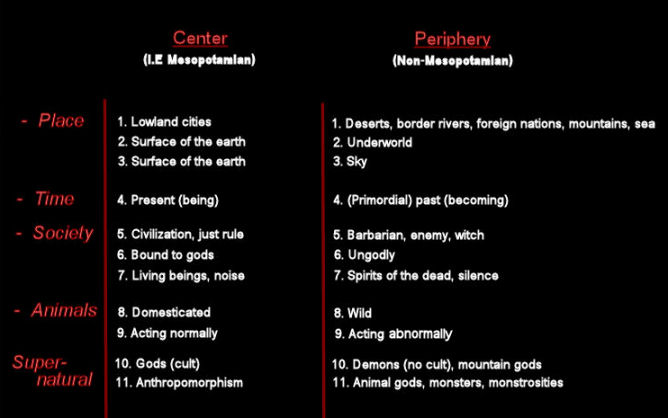

the Mesopotamian's own perspective of themselves. The author has

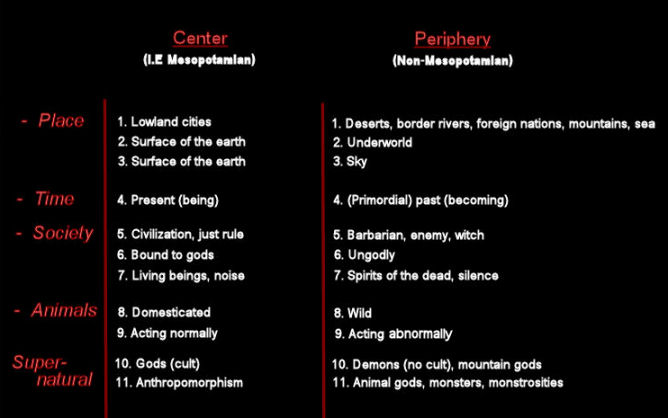

charted the following contrastive elements which play a part "in

the native definition of Mesopotamian civilization":

As we can see, the left column (Center / Mesopotamian) represents

the ancients own notions about themselves, and what defined their

society. The right column is what Wiggermann terms "the shadow

side", all that the Mesopotamians considered 'other', the

opposite in each case of what they saw as their society. Of course,

we might deduce that while these things were contrastive, they

had an important role in defining what was Mesopotamian, if only

by being tangible examples of opposition. The right column is

just as instructive as the left therefore.

The author continues explaining that the two spheres do not normally

intermingle, but entities from the right column such as enemies,

wild animals, spirits, demons or monsters, infringe on the civilized

world - sometimes this is seen as a sign of divine displeasure

with a king or inhabitants. There is no impassable boundary between

the two spheres. The dead, indeed, "have no choice in the

matter, but must travel westwards through the desert" says

Wiggermann.

The subject of direction that the dead must travel is made complex

by the fact that notions of the netherworld underwent significant

changes from the original Sumerian netherworld located in the

mountain land, and the Semitic concept which places it under the

earth. About the former concept, the author says: "the most

common term for the Other World is kur, "mountain land",

which is in opposition to kalam, "our country". This

kur is where the dead go, and where rebellious mountain gods,

demons, and monsters are at home. Human enemies as well descend

from the mountains, and sometimes they are so dreadful that they

cannot be distinguished from demons... Both steppe and mountains

harbor a host of wild animals which are hunted and killed by Mesopotamian

rulers from the late Uruk period onwards; they were brought to

the capital as spoils or tribute, and symbolically express the

wide extent of just rule. Assyrian kings make statues of some

of the more exotic animals, and stand them as guardians of their

palaces as apotropaic monsters."

All that is from the perphery is stands in defiance of the gods

- and in opposition to the Mesopotamian people therefore. Commenting

again on the right hand column, the author states that the "properties

of the elements in the right hand column of our scheme are more

or less interchangeable; that the inimical fuses with the demonic,

and the peripheral with death and the underworld, thus resulting

in a more or less unified image of all that is evil and conspires

against civilized life, i.e. zi-ša3-gal2. The geography involved

is marked by an increasing loss of empirical content, until finally

the Land of No Return is reached; this is the realm of the dead,

whence no traveler can bring back reliable information."

Wiggermann's discussion advance's to discuss instances of other

world imagery on Mesopotamian iconogaphy, and most fascinating

this preasents new insight on the famous bull-headed lyre from

Ur. For more, the book containing "Scenes from the Shadow

Side" can be purchased through Eisenbrauns

or one can inquire with persons familiar with the work at the

Enenuru

disucssion board

Propects

for Resurrection in Mesopotamia

As a side note, some brief consideration is given to the notion

of resurrection in Mesopotamia. The reader should be careful to

note that our treating this topic should not be taken as a confirmation

of any solid Mesopotamian precedent for notions that find common

play in Christian religion - however we seek to objectively weigh

the question. A recent article entitled "Mesopotamian Roots

for the Belief in the Resurrection of the Dead" appeared

in the publication "Relgion Compass" which presents

anthropological material on Ancient religion, frequently focusing

on Mesopotamia. The author of this article is Benjamin Studevent-Hickman,

an ancient historian specializing in the study of ancient Mesopotamia;

he currently serves as a Lecturer on Assyriology at Harvard.

The author begins by contextualizing resurrection beliefs within

the greater history of Western religion. We know the belief in

the resurrection of Christ was a major tenant of Christian faith

- less familiar may be the aspects of the belief within early

Judaism. Studevent-Hickman informs us that upon the Jews return

from the exile (the exile in Babylon), a belief in the resurrection

of the dead became more and more prevalent in certain Jewish factions:

the Pharisees and the Essenes. The author writes that while the

Sadduccees maintained no belief in resurrection of any sort, the

Essenes in the post-exilic period believed a spiritual resurrection,

and a third group, the Phrarisees, actually believed in the literal

and physical resurrection of the dead. This notion of physical

resurrection reached it foremost proponent in the person of Paul

the apostle, a Pharisee who would become demonstrably instrumental

in establishing the doctrine of the resurrection of Christ - in

turn, this was fundamental in the notion of the resurrection of

the Christian soul after death. So where does this Phariseetic

belief come from ultimately?

Studevent-Hickman asserts that the real root of the notion of

resurrection (that the dead can come back to life of some unspecified

sort, and not as any sort of salvation as the idea comes to be

with later extrapolation...), the simple idea of resurrection

was, in origin, Near Eastern: and not essentially Canaanite or

Persian as has sometimes been suggested, but Mesopotamian.

Death and Return in Mesopotamia

The author makes it clear that in Assyriological circles, the

idea that any of the Iraq civilizations believed in physical return

has little currency. Not only is there little study on this particular

question, some have flatly denied that there is any evidence for

such a belief in extent Mesopotamian literature. He chooses to

differ here however, and it may prove worth debating -

The author extends first an explanation of the Mesopotamian concept

of the Body and Soul, here he follows Abusch's analysis of the

Atrahasis material (for a summation of Abusch 1999, see this thread

Reply #9). Coming to the question of resurrection in Mesopotamia,

the author puts this into Mesopotamian terminology - it is to

return from the Netherworld, which itself is sometimes termed

"The Land of No Return." But how often do entities in

fact return from this very place in Mesopotamian literature? How

often do things come back from the dead? The author lists these

instance of divine return:

Cases of Divine Resurrection

* Namtar, the vizier of Ereshkigal travels freely to and from

the Netherworld.

* Utu has this same ability

* Inanna is released from the Netherworld (returning from the

dead) on gaining Dumuzi as her substitute. Inanna's case is particularly

indicative of a physical resurrection as she is a "slab of

meat" down there, a corpse, before Enki's creature revive

her with the plant and water of life.

* Geshtinanna goes to and returns from the N.W. semi-annually,

in concordance with her brother Dumuzi who also returns - in academic

literature, Dumuzi is often considered the proto-type of the dying

god type (Christ being another example).

More important, the author says, are the cases where humans,

not gods, have the potential to return to the land of the living:

Cases of Non-Divine Resurrection

* The cases where Ereshkigal and Inanna threaten to raise the

dead that they might "outnumber the living."

* The instance when Enkidu is physically raised in "Gilgamesh,

Enkidu and the Netherworld" and he speaks with Gilgamesh.

An additional element considered here is the poignant observation

that incantation and medical texts in Mesopotamia abundantly attest

to the belief that ghosts (largely discontented malignant ghosts)

could travel to and from the netherworld with more ease perhaps

than even the deities. He references Scurlock in order to state

that some cases of a ghost contacting a victim strongly indicate

that the contact was thought to be physical, which lends ghost

afflictions to a resurrection like (on the other hand, other incantations

give descriptions of contact that could hardly be more than metaphorical.)

However, I would disagree with the author in assessing these last

instances as offering "important" perspective on this

matter. Referring again to Katz 2003, that author stresses that

the NW is known by the epithet "the land of no return"

adding "excepting a few deities who managed to leave the

Netherworld in exchange for a substitute or ransom, only evil

spirits could leave the realm of the dead and move freely back

and fourth. The exception to the rule indicates that there is

a way out, but that one does not come from the netherworld alive."

Here Katz has stuck on a good point that Studevent-Hickman may

have overlooked - that being the fact the deities coming back

(Inanna, Dumuzi and Geshtinanna) are reliant on substitutes to

take their place in the netherworld - and so they are not precisely

achieving a victory over death, rather they are trading the grip

of death to some other unlucky soul. While they may live often

on a temporary basis, this sort of resurrection is a step again

away from the sort we see in later religions, if not more. Additionally,

Katz statement that "one does not come from the netherworld

alive" is made more potent by her assertion that the principal

example of a returning mortal, Enkidu, did not come back bodily,

but rather as a ghost or in a dream. As in the festivals of the

ghosts, we are dealing with the return of spirits.

Concluding

That said, despite ultimately hesitating about the idea of any

notion of physical resurrection in Mesopotamia, we would still

agree with Studevent-Hickman that ideas of resurrection in Mesopotamian

(especially Inanna and Dumuzi) may have traveled to the Pharisees

and from there down to Paul - after all, even if the Mesopotamians

lacked solid precedent of mortal resurrection in their beliefs,

they knew divine resurrection in specific contexts, and Jesus

to Paul was not to be thought of as less than divine.

|